Edward Ka-Spel’s brilliance with The Legendary Pink Dots is to introduce us to isolated characters and then immerse us in their world-view through expansive and mysterious soundscapes. He begins with the most restricted, infinitesimal point of consciousness and then slowly expands it outward towards a state of ‘cosmic consciousness’ (to use the phrase of 1960s psychonauts). Musically, he often follows this template of expansion, with simple melody lines repeating and layering in increased complexity of texture. Much of the LPD’s music is an undertaking to help the listener (and perhaps composer) escape his/her own head. Lyrical phrases, musical motifs, album titles and themes recur across decades, but tonal shifts between albums are slow and subtle. Hopefully, The Legendary Dots Project, like the Residents and Sparks projects before, will provide the keen reader and listener with a giddy entry-point into the Legendary Pink Dots’ musical world. Fulfil the prophecy!

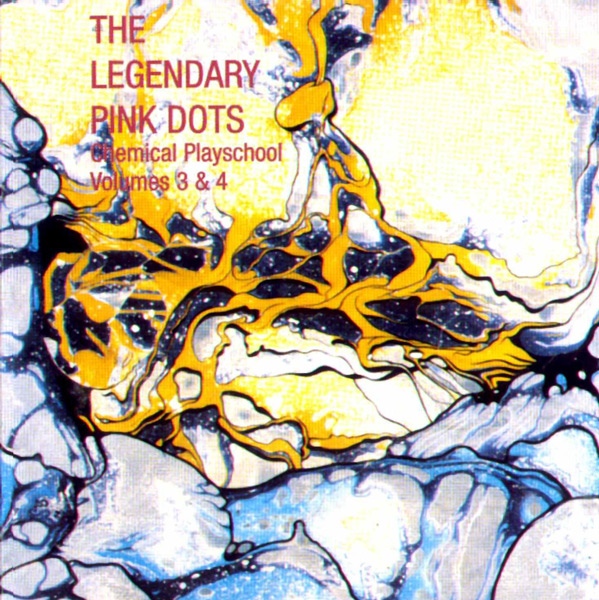

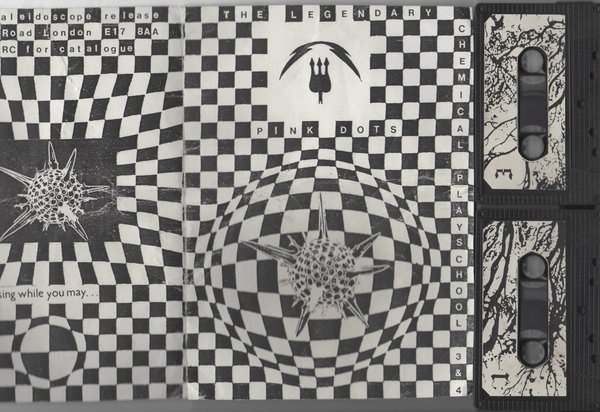

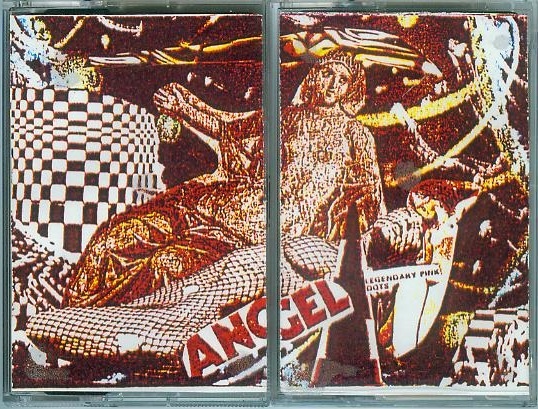

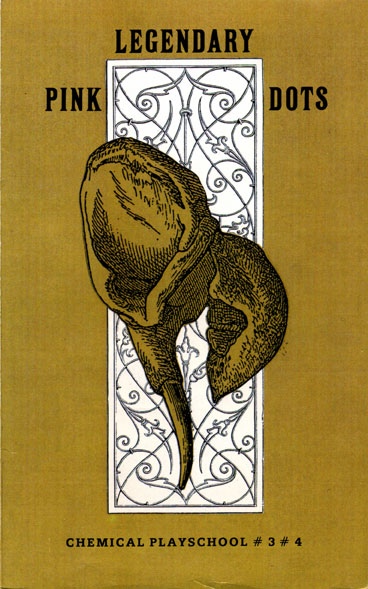

Tom: Chemical Playschool 3 & 4 is another gargantuan release: disparate in its balancing of marathon soundscapes with off-kilter tunes and a greater than before quota of politics.

‘The Top’ upends the “kitchen sink”, associating Joe Lampton with ‘synthetic manliness’. ‘Neon Gladiators (Version 1)’ is tremendous proto-acid house, with gadding bass and dovetailing squalls of synth and guitar. Chaos is evoked; capsizing walls, condemned criminals and a reference to statuary. There’s gleaming, off-centre organ that lends this deranged stomper a graceful, woozy undercurrent.

‘Obsession’ is one of those occasional LPD relationships songs, and is a typically dank scenario of break-up and solitude. Following the split, he ends up “playing patience on the floorboards” – not the only account of Garbo-esque solitude on this album. It’s a glum guitar confessional not all that far from Peter Hammill on Over (1977). There’s a terse, metaphorical economy to the lines: “I had a picture of you. I sliced it up in two and half my love went in the bin, with the letters.” There are naturalistic references to the offending minutiae: burning the eggs, smoking in bed, buying trivial knick-knacks. Taking not just the records, but the cat: ‘My charity’s all gone, like those records that you stole when you rolled up our relationship and slipped out unannounced. Christ! You even took the cat.” It’s a partial perspective, as is inevitable with such rejoinders.‘When the Clock Strikes 13’ concerns an idealised, desperate romance, viewed as if a French film take on Bonnie and Clyde: a defiant stand against a hostile world, a fugitive couple up against it. Like Tracy Barlow and Rob in Coronation Street, as almost was – in recent episodes of that longest of ongoing British narratives.

‘Curse (The Sequel)’ has stifled, urgent imperatives (“curse your daughters”, “slaughter with a glance”) giving way to baleful declaratives (“I’ve got your picture. I’ve got the pins”). It’s one of those early LPD guitar-led songs not far in form from Television Personalities, but the lyrical content is infinitely more macabre. The effigy inevitably suggests burning or hanging. The wistful, plangent guitar tune transmogrifies into an ambient murk. We catch snatches of Arthur Freed-Nacio Herb Brown’s ‘All I Do Is Dream Of You’, transporting us back into Broadway-Hollywood dreamland. A song recorded not just by Judy Garland, Dean Martin, Alma Cogan, Johnnie Ray, Doris Day and Twiggy, but by Al Bowlly back in 1934 – its year of publication – and Chico Marx in the following year’s A Night at the Opera. This version is from the cartoon flapper character Betty Boop, who was subject of sanitisation by the Hays Code from 1935. This evocative sampling is supplanted by gently wheezing, choked windbag organ; rather like something James Kirby, aka. The Caretaker/The Stranger would come up with: sublime unease, or an uneasy sublime. ‘Hideous Strength’ is a tale of a man transformed into a lion – and then being incarcerated, echoing the Greek myth of the lovers Hippomenes and Atalanta being metamorphosed into lions by Cybele. This song’s leonine figure is more rampant than dormant, proclaiming to be “king of all the jungle”, linking with the lion’s omnipresence in royal arms of medieval and Tudor monarchs. The lion may be significant, in that the title echoes C.S. Lewis’ science fiction novel, That Hideous Strength (1945), which assailed scientific materialism running amok, destroying spirituality in its wake. It has striding Aslan-ish bass, there’s more glistening organ like in ‘Neon Gladiators’. “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. All good kittens go to heaven!” This memorable, repeated chorus ought to have landed the LPDs a number one single; better this than ‘Too Shy’, ‘Red, Red Wine’ or ‘Baby Jane’, surely. A piercing three-note synth riff (03:11-03:25), and emotive ‘miaow’s are where it should have been at, instead of spandex, smugness and inexcusable blonde hairdos.

The instrumental ‘Film of the Book’ has a richly evocative, almost Eastern sounding, keyboard refrain – patiently, celestially repeating. It is our passage to ‘The Tower’, our introduction to Ka-Spel’s ‘Tower’ mythology. The titular edifice is impregnable, ‘a beacon in the dark’. ‘The Tower (Version 1)’ details seemingly unfathomable incarceration: ‘And no-one names a crime committed, no-one blames a soul. Their cases heard so long ago – forgot about parole.’ Josef K’s bleak situation in Kafka’s The Trial comes to mind: with its labyrinthine justice system – marked by perpetual deferment and opacity. The constantly repeated closing refrain: “No one has the key to the Tower” is a very Kafkaesque scenario of impersonality and hopelessness. This first Tower track is an inexorable twelve minutes of anti-progress towards chugging emptiness. The second ends with archaic, military-style horns and ‘salutes’. ‘Tower 2’ is a bleak scenario of monkey torture and a man-eating Doberman. Humanity is de-personalised, police state authoritarianism runs rampant, enabled by democracy: “And there’s weeping in the queue, and Lady Gwyneth’s weeping too – sickened, yet she voted blue. She knows it. And night patrols are doing rounds. There’s Tower complex, Tower Towns. Population’s going down, but we’re great again.” This implies the unemployment and severe population decline suffered by most British cities in the 1970s and 80s. As well as the Falklands War and subsequent facile economic ‘boom’, leading to a hollow proclamation of Britain’s renewed ‘greatness’.

As early as January 1979, cultural theorist Stuart Hall had identified an ‘authoritarian populism’ as one of the dominant strains of Thatcher’s politics. Hall described her politics as ‘unlike classical fascism’, in ‘retaining most (though not all) of the formal representative institution[s] in place’, while simultaneously constructing ‘around itself an active popular consent’. This involved associating with simplistic, homely notions – national fiscal policy as akin to a household budget, ‘HOME IS WHERE THE HEART IS’ – and a strong law and order agenda: getting the police onside and enlisting their more reactionary tendencies to combat left-wing opponents.

The idea of property ownership was dear to Thatcherite hearts. In August 1983, the Times article entitled ‘Home is where the heart is’ reported that, by the end of 1983, 59% of homes in the UK would be owner-occupied, 3% up on 1981. Nine out of ten of those aged 25-34 saw home ownership as the ideal. Ka-Spel was 29 and clearly not one to write paeans to home comforts.

The 59-second ‘Glad He Ate Her’ continues the dystopian focus. It is a brief, disturbing vignette, with the objects of the ‘screwing’ left ambiguous: “They threw off their dressing gowns, and screwed for the Empire. Screwed for the Queen.”

‘Tower 3’ begins with “The echo of a thousand marching boots hammers on the air.” It’s a queasy, frenzied account of ‘entitled’-feeling boot-boys who are “singing anthems, chanting oaths and [who] whistle as Salome lifts her skirt because they’re ‘real’ men and they’re healthy, happy… own the place.” A mythical striptease viewed by proprietorial 1980s men. The policeman – a “uniform” – tells them their petrol bombing of opponents is against the Law but they’ll “ignore it this time. Peace Krime’s got to be official!” Thus, collusion between far-right bovver boys (“Keep it pure, keep it white”) and the authorities is made clear. They can – and will – put down non-whites and CND.

EKS details a living room – it is unclear whose – with Playboy-style pin-ups, pictures of the Queen and a homely proverb (“HOME IS WHERE THE HEART IS”) forming a tellingly contradictory collage: signifying authoritarian populism. The song goes onto detail a cowed, unquestioning public turning blind eyes, while patriots stay indoors, warmed by their leaders’ promise of a new ‘Golden Age’.

‘Lullaby for Charles’ Brother’ emerges from arcade bleeps. It could be a seventeenth century English folk song, but rendered on minimalist synth sequencer and simulated woodwind. It concerns an urban political protest from a disgruntled misanthrope, raging against the police (‘piggies’) and as inevitably doomed as the miners were at Orgreave: “Drew out a carving knife for his course: piggies in blood across the wall. Mummy was shocked but he’s immortal, four page pull-out in the Sunset.” There’s a pointed refusal to directly refer to Murdoch’s regrettably successful tabloid. Unlike the miners at Orgreave – as depicted in the recent documentary Still the Enemy Within – there’s little sense of collective struggle. The protagonist’s grievance is unspecified and his link with the demonstrators is ambiguous.

The magnificently titled ‘Expresso Curfew’ suggests the hegemonic dominance of consumerism, with its intermingled Big Ben chimes and science fiction bleeps. Future and past. Time and space. Binary associations and oppositions assert themselves. An enforced adherence to a system that allegedly grants its citizens ‘choice’ is implicitly critiqued. Indeed, ‘The Plasma Twins’ develops into what sounds like a halting ballet of the TARDIS roundels being rounded up and put to humiliating work by the Krotons. ‘Surprise, Surprise’ includes an ephemeral section of ethereal female vocals, followed by ricocheting percussion and, again, that ghosting organ. Flags, medals, bouquets, limousines, the banal ‘Golden Age’ dream: all detonated in a Goon Show-esque explosion.

‘Premonition 10’ is an immersive thirty-two minutes, a somewhat more percussive variant on the deep ambient of :zoviet*france, who I recently saw headline the Friday of Newcastle’s TUSK Festival. That performance transported you to a rainforest; this propels you into the star-spangled ether and the grimy basement – often simultaneously!

‘Cherry Lipstick’ adopts the ‘Film of the Book’ refrain, overlaying corporeal concerns onto what was otherworldly: “I like you with your make-up on”. “Let’s paint the town together” adopts the American phrase ‘to paint the town red’; concerning celebrating without inhibition and which originally alluded to a red light district permeating the whole town.

The closing ‘The Glory, The Glory’ evokes Chris Marker and Alain Resnais’ Statues Also Die, and directly misquotes its title, enlarging the statues’ stature. History will not devour these mythical statues. A potent, swelling organ enters alongside the adjective “naked”, as it becomes clear the statuary is sentient. These effigies are “waiting for their turn to rule a world where nothing speaks and nothing’s small – nothing’s ever worshipped”. It’s an unnerving picture, as the statues become gods in a world of silence, “on their own, alone”.

Adam: 1983 was the last year that Edward Ka-Spel would spend in London before he decamped to Amsterdam and you can tell listening to Chemical Playschool 3 & 4 that he was sick to the back teeth of living in Thatcher’s Britain. While it is nigh-on impossible to make any encompassing judgements about a compilation that is approximately two hours long, many of the tracks feel strung-out and disconsolate, even by the Dots’ typically restless standards. There are slow, contemplative pieces characterised by foggy drones and Ka-Spel’s plaintive knowing whisper, such as ‘She Said’, but these are islands of uneasy respite amongst long stretches of skittish dissonance. Even a piece like ‘The Plasma Twins’, that starts out sounding like one of the Dots’ cosmic soundscapes – in this case a rather lovely Brian Eno-ish composition, though everso slightly threatening – ends up transforming into a looping cycle of whining guitar that sounds like a wasp trapped in a kazoo and an ominous, shark-toothed bass line that would sit comfortably (ha!) somewhere on Portishead’s Third (2008). The narrator of ‘The Plasma Twins’ sounds tetchy and testosterone-charged in the grotesque, predatory way we previously encountered on ‘Thursday Night Fever’ on Only Dreaming (1981) but here he is diminished and vampiric, clawing and needy. His invitation “I’ll show you my muscles, if you give me your corpuscles. I’ll have your blood, and you’ll have my seed” repels, though Edward sounds seductive and solicitous.

Elsewhere, the album’s lyrics offer flights of fantastical release from suburban squalor, which warp into troubling hedonistic visions or hysterical reveries of violence. The opening track on my edition of the album, ‘The Light In My Little Girl’s Eyes’, begins with the lyrical equivalent of an establishing shot that tracks across a city’s streets, taking in the smell of coffee, shops stacked with stereos and the sun dancing on the chromium of limousines. Lights turn red, a car crashes, and in a moment of strange alchemy the paving stones turn to playing cards and the singer finds himself ushered away to the palace of “the blackest queen”. Soon, in the throes of animalistic passion, they are tearing chunks of flesh from each other, gobbling down body parts, like the two teenager lovers in the infamous Supernatural episode ‘My Bloody Valentine’ (2010). What starts as a simple procession of chords on the keyboard builds in stages, adding in brisk, purposeful drumming; a gloomy yet funky bass courtesy of Roland Calloway; vocal echos; tight little flurries of guitar; weird treated keyboard sounds… until Ka-Spel is calling out a repeated refrain of “Brighter now! Brighter now!”, the name of an album from the previous year, that indicates how early in their career the Dots’ began building a self-referential mythology across their discography.

‘Neon Gladiators’, which sounds like ‘Crosseyed and Painless‘ from Talking Heads’ Remain in Light (1980) played on low battery in a dingy video arcade, conjures a scene of shag-pile carpeted opulence before summarily smashing it to pieces with a murderous cavalcade of sword-wielding living statues. Similarly, the party of chin-wagging socialites and military bigwigs in ‘Surprise, Surprise’ is gleefully blown to smithereens by a present-wrapped bomb, although the effect is rather more like a scene from The Young Ones (1982-1984) than The Anarchist’s Cookbook (1971) especially since Ka-Spel manages to crowbar throwaway innuendo (“it was a master bake”) into the lyrics.

On this collection, outcasts and non-conformists don’t fare much better than members of the establishment, however. ‘Hideous Strength’ is a character portrait of an individual that society would label “crazy”, the type of which characterises the Dots’ later 1985 album Asylum. Ka-Spel’s sympathies are clearly with the deviants, not the “army of the upright” (to use a phrase of Virginia Woolf’s) though he never outright romanticises mental illness or alienation. Leo, the character in ‘Hideous Strength’, believes himself to be a lion… a natural extension of his taste for raw meat and a conclusion he reaches by observing his long hair in the mirror. As an interesting aside, his transformation is the same experienced by the narrator of The Residents’ ‘On the Way (to Oklahoma)’ on their 2005 album Animal Lover. Leo is clearly very unwell, but his vibrancy and virility seems far healthier than the masculinity of the vampiric narrator of the aforementioned ‘Plasma Twins’ or the moody brooding of the love-sick obsessives of ‘The Waiting Game’, ‘She Said’ or – indeed – ‘Obsession’. Another alienated (anti?)hero is the lone activist of ‘Lullaby for Charles’ Brother’. The song sounds like a nursery rhyme played on keyboards submerged underwater. The talk of ‘piggies in blood across the wall’ and the name Charles, summoned the spectre of Charles Manson to my mind. Indeed, there is something of the soured idealism of 1969 on this album… a film by Jean-Luc Godard watched on a lossy VHS cassette.

With the density of lyrics on Chemical Playschool 3 & 4 it’s very easy for the listener to disengage from the music, experiencing it as background furniture for Ka-Spel’s storytelling. This becomes especially pronounced in his later solo work, in which lyrics are sometimes spoken rather than sung and longer tracks like ‘The Voyeur’ from 2012’s Ghost Logik essentially function as short stories. Indeed, this review has focused perhaps a little too exclusively on the album’s lyrics and it is worth turning to the instrumental tracks to give them the consideration they deserve.

‘Film of the Book’ is a deeply lovely mirage of a song, sounding like the music that might play in some celestial cathedral in a Japanese RPG. It’s crystalline and plaintive – Pachelbel’s ‘Canon in D’ as dreamt by an alien civilisation. I feel as though I might have encountered in before on an earlier release, but it hardly matters when the music is so soothing, especially on an album that often makes for uncomfortable or anxious listening. ‘Collapse’ sounds crueller and more sardonic – an insidious little tune that recalls the mangled and diminished refrains of Fats Waller on the soundtrack of David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977). It segues very pleasingly into the non-instrumental track ‘Tower 2’.

The wonderfully named ‘Barbed Obituary’ is a wash of glooming keyboards. ‘Expresso Curfew’ might have been recorded in the engine rooms of a Vogon Constructor Ship / the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. ‘The Bride Wore Green’ is curious but pleasing and reminds me a little of one of my favourite early Dots tracks, ‘Voices’, if only for the wind effects. ‘Premonition 10’ is a bewitching medley-cum-soundscape of backtracked choirs and percussive drums. It sounds like it might have been built from the same Notre Dame field recordings that composed ‘Basilisk 2’ on the 1982 album of the same name. ‘Grind’ is another long soundscape, though only really gets interesting near the end of the track. It would, to its credit, fit in nicely alongside the more abstract pieces on BBC Radio 3’s Late Junction programme (which often features musical treasure and is worth checking out). ‘Apocalypse Gone’ is like a horrible deconstruction of a Shostakovich violin concerto. Finally, ‘It’s Raining … Again’ contains some really interesting sounds, the origins of which are difficult to discern. It’s non-essential, but would make super background music for a David Firth animation (which is meant in all earnestness – it’s a track that demands visuals).

Chemical Playschool 3 & 4 is long enough that it seems reasonable to save discussion of the ‘Tower’ tracks for The Tower (1984) album itself, where they acquire more muscular production, bring Ka-Spel’s vocals to the fore and really come into their own. It is fascinating to hear these tracks emerge from the foggy production of the Dots’ very early years. They become more direct, more visceral and acquire an even greater degree of sardonic bile and political desperation. They also become funkier. The tracks – ‘Tower 1’, ‘Tower 2’ and ‘Tower 3’ – are wonderful here, of course, but they’re swamped by the surrounding material. Although it is something frustrating when a band revisits material, I’m very glad that the Dots decided to do so with these tracks.

So, Chemical Playschool 3 & 4 is a heady, disorienting and often gloomy mix. The quality is high, but it’s a lot to imbibe in one sitting. Of particular note are Ka-Spel’s vocals. He manages to be theatrical without ever being anything less than convincing. A track like ‘She Said’, which I otherwise find musically forgettable, is saved by Ka-Spel’s cracked delivery and mournful tones. As a listener you’re often thrust into the strange position of sympathiser; bemused on-looker; victim; co-conspirator, by turns. He’s knowing, tainted and faintly abject on the odd nasty ditty ‘Glad He Ate Her’. He sounds like a drugged and emaciated ghoul on ‘The Top’, with its talk of a belly full of seeds. On ‘Cherry Lipstick’ (which reprises ‘Film of the Book’) he is needy, wretched, pawing. He cries and whispers like Robert Smith on ‘Just Passing Over, Lovely…’

To quote T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922): “he do the police in different voices“.

Matt: Well, obviously, “Hideous Strength” is my favorite track — you can never go wrong with meowing in a song. But I dig the synth line, and the story, which as Adam points out is similar to “On The Way (To Oklahoma)”, one of the handful of Animal Lover tracks I quite like. And what with the Pope recently saying that animals can indeed go to heaven, it’s as timely now as ever.

As for the rest of the album — it’s another long one, but, again, a collection of good songs rather than filler. “Neon Gladiator” has a wonderful driving, poppy beat combined with the noises of destruction — The Important Sound of Things Falling Apart. Honestly, it’s one of the LPD songs I could see being a hit had things properly aligned — though I’m not sure if Ka-Spel was even particularly interested in that. I kind of get the impression that his main driving force is making music, and if anyone else happens to like it, all the better. But I imagine that even if there were a worldwide campaign to get him to stop (And in that case: The world would be WRONG) — he still wouldn’t. He’d continue through making records with his blinds drawn to hide the ocean of picket signs outside his door. And that’s awesome.

I also love the texturing on “Film of the Book”. While instrumental, it demands attention. It leads into “Tower 1”, using the Tower of London as its central metaphor and is about oppression — which makes me wonder about the use of so many songs to feel oppressive (in a good way, though — speaking artistically here, not just “oh no, I have to sit still for two and a half hours!”). A lot of the material on Chemical Playschool 3 & 4 has a similar sonic pallate — and I guess you could say that about the Dots’ other material up to this point as well — which means you’re in a dark, stuffy, murky world. And given his criticisms of Thatcherite Britain, it’s a political world as well, and it’s easy to see the more fantastic tracks (like, again, “Hideous Strength”) being an expressionistic explanation of the feel of being under Thatcher’s thumb. I’m a little young to have experienced Reagan’s America firsthand (or, rather, though I was alive for his entire Presidency, I wasn’t terribly politically aware at that point, starting as an infant and ending his run at the age of eight) — but we’re still living with the decisions he made. The homeless problem can be linked back to his closing of the mental hospitals, he was a strikebreaker which kneecapped labor in this country, he hemmed and hawed on AIDS, the list goes on. And seeing as he and Maggie were best buds (that and a healthy Chumbawamba fandom on my part filling in some of the details), I’m imagining that it was similar across the pond as well.

That said, too, it’s not just as a nostalgia piece that this method and material works. If you listen to “Tower 3”, it’s particularly relevant in 2014 America, despite being about 30 years old — “In the living room a picture of the queen nestles in between Miss August and a placard saying HOME IS WHERE THE HEART IS. (Keep it pure, keep it white. Keep it free of undesirables because freedom is so valuable and getting scarcer.)” Sound much like, say, Ferguson, or Eric Garner, or hell, just the anti-Immigration bullshit from folks like Sheriff Joe Arpaio, folks who want to be allowed to card Latinos to “make sure” they’re legal — which doesn’t sound like racially motivated harassment at all, no sirree.

I think it’s this feeling that makes it kind of hard to listen to this album all in one go. As relevant as it is today, I almost kind of want to go into the Escapism World and listen to happy, shiny music to take my head off things. But I also know that that’s NOT the way to go, since it’s that kind of thing that keeps the status quo. So, dare I say it, but this album might be actually Capital-I Important?

Either way, though, it should be listened to, even if you have to break it up into 45 minute chunks.